Common Hunting Injuries and Their Treatment

ISSN 1059-1865 Voulume 29 Number 1

By Jeff DeBellis

To those who don’t hunt, loading a weapon and marching off into the icy pre-dawn woods where dozens of other hunters are waiting with rifles pointed in countless directions may seem like an unnecessary risk in an era when good-quality, grass-fed meat is available in nearly every grocery store. True or not, nearly fourteen million Americans set off into the woods to go hunting every year. Countless others are hiking, biking, skiing, or backpacking in those same woods during hunting season. Hunting injuries are rare, but they are increasing. In the two decades between 1987 and 2006, they rose twelvefold. The causes vary widely, and, at times, the research appears to contradict itself. What is clear is that a little bit of prevention and basic knowledge of treatment goes a long way. A brief review of the research found six common categories of hunting-related injuries: gunshot wounds, tree stand falls, knife wounds, heart attacks, and arrow impalements.

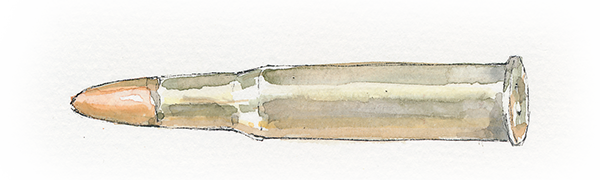

Gunshot Wounds

The majority of hunting injuries are not firearm-related. Still, a number of fatal and non-fatal gunshot injuries do occur every year. About half of these are self-inflicted. One of the easiest things to do to prevent being accidentally shot by someone else is to wear blaze orange. One study in New York found that 94% of victims of firearm injuries were not wearing blaze orange (New York is one of only eight states that does not require hunters to do so). Avoiding alcohol while hunting should go without saying, but it plays a role in about 10% of hunting injuries. Other common tips are to treat every gun as though it is loaded, never point a gun at anything you wouldn’t want to kill, and keep your finger outside of the trigger guard until ready to fire.

At the very least, gunshot wounds cause either puncture wounds or impalements, depending on whether or not shrapnel remains in the body. Sometimes it’s not easy to tell if it has. At worst, these wounds could cause fractures (including spinal), cardiothoracic trauma, and, of course, death. The majority of gunshot wounds from hunting accidents occur in either the arms or legs. Even these could be fatal because of heavy bleeding and result in hypovolemic shock. If the patient’s airway and breathing are not affected, the first priority is to stop the bleeding by applying a pressure dressing. Elevating the wound above the heart is not always taught but will do no harm. Digital pressure should be used if necessary, and, as a last resort, a tourniquet or hemostatic agent. Clean the exposed part of the wound as well as possible, bandage it, and evacuate the victim as rapidly as possible.

family also includes the festive poinsettia and the Cathedral Cactus.

family also includes the festive poinsettia and the Cathedral Cactus.